GHR background paper for the first informal meeting (19 August 2019)

Over the last seventy years, the United Nations adopted many human rights instruments, bodies of principles, declarations, conventions, and dozens of monitoring mechanisms and procedures. But, on the spot, victims, witnesses, human rights defenders and organisations continue to work under difficult conditions. Massive human rights abuses persist around the world. Indeed, there are still gaps between the UN standards and the follow-up of their decisions. It is time for implementation. This has to be done by the country itself, which implies a need to develop national protection systems and national capacities.

The development of human rights in the UN has not been, and will never be linear. There have been periods of progress and years of regression often concluded with confirmations during major events, such as the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights.

After all, these ‘ups’ and ‘downs’ are not surprising. Major political developments often lead to drastic changes in the human rights policy of many States (see the former Latin American military dictatorships becoming strong supporters of human rights). With the globalization new needs and priorities emerge, object of political confrontation. Moreover, Governments generally don’t like to be called to order by an increasingly effective human rights system, in particular by the treaty bodies and the special procedures.

The ‘ups’ and ‘downs’ also coincide with specific conditions in the UN system. Thus, at the end of the 70s, we had a brilliant UN Secretariat. In the 70s, 80s and 90s, we had also a Sub-Commission producing in-depth studies, draft declarations and conventions, proposing additional procedures and alerting on massive human rights abuses. The Secretariat and the Sub-Commission then actively supported victims, witnesses, defenders and organisations, who came not only to raise their concerns, but also to make proposals.

We are currently in a ‘down’ phase. The UN human rights system is under increasing pressure from a growing number of States. This has started during the 90s, with the (unfortunately successful) attempts to reduce the Sub-Commission to silence. After this, hardliner States focused on the Special Rapporteurs. Many were accused of ‘partiality’ and ‘subjectivity’. Some were threatened, already in the 90s, like Mr. Dato’ Param Cumaraswamy (Rapporteur on judiciary, persecuted by his own country, Malaysia) and Mr. G Biro (fatwa against him in Sudan), and more recently, Ms. V. Tauli-Corpuz, Rapporteur on indigenous peoples, put on the list of ‘terrorists’ in her country, the Philippines. A code of conduct was adopted in 2007, for the mandate holders, and not for the States committing crimes.

To further avoid the debate, many States then targetted NGOs and defenders, by misusing the anti-terror legislation to accuse human rights NGOs, defenders, and sometimes even victims and witnesses of ‘terrorism’. Legislations prohibiting foreign funding were introduced in many countries, in all the regions. And, in the Human Rights Council and its mechanisms, hardliner States multiply the obstacles to the NGOs, who provide the human rights mechanisms and procedures with authentic, verified, and therefore credible information. Reprisals against them have become an urgent issue.

States also target the treaty monitoring bodies. In its Resolution 68/268 (2014) on ‘Strengthening and enhancing the effective functioning of the human rights treaty body system’, the UN General Assembly decided to consider the state of the treaty body system no later than six years later, to review the ‘effectiveness of the measures taken in order to ensure their sustainability, and, if appropriate, to decide on further action to strengthen and enhance’ its effective functioning. And, whilst the Committees did a lot to improve their working methods, the financial weapon is being used to try to cancel their next meetings.

UN human rights standards are also under pressure, both inside and outside the UN, as exemplified by the attempts to re-define the concept of torture; to obtain more restrictions to the freedom of opinion and expression; to limit the freedom of religion or belief; to challenge women’s rights; and to oppose the protection of certain human beings because of their sexual orientation. New thematic resolutions were passed in the Human Rights Council (‘HR-Council’), re-defining the human rights standards, such as the ones on development (to realize human rights, China); on the ‘Win-win’ principle (dialogue instead of confrontation); and on human rights of the family (Egypt, Saudi Arabia). The Trump Administration recently joined this movement, starting a review of the role of human rights in US foreign policy, and appointing a commission expected to elevate concerns about religious freedom and women’s rights. To avoid examining massive human rights abuses, hardliner States, whose number in growing in the Human Rights Council, use again the arguments of sovereignty, non-interference and cultural pluralism and/or diversity’.

There is urgent need to think through a strategy to re-establish the centrality of human rights at the United Nations.

GHR Brainstorming process

GHR General Assembly of 19 June 2019decided to initiate a brainstorming process on these developments, together with individuals, partners sharing the same concerns, such as UN experts (several current and former mandate holders of special procedures, and of treaty bodies), academics, and several NGOs experts.

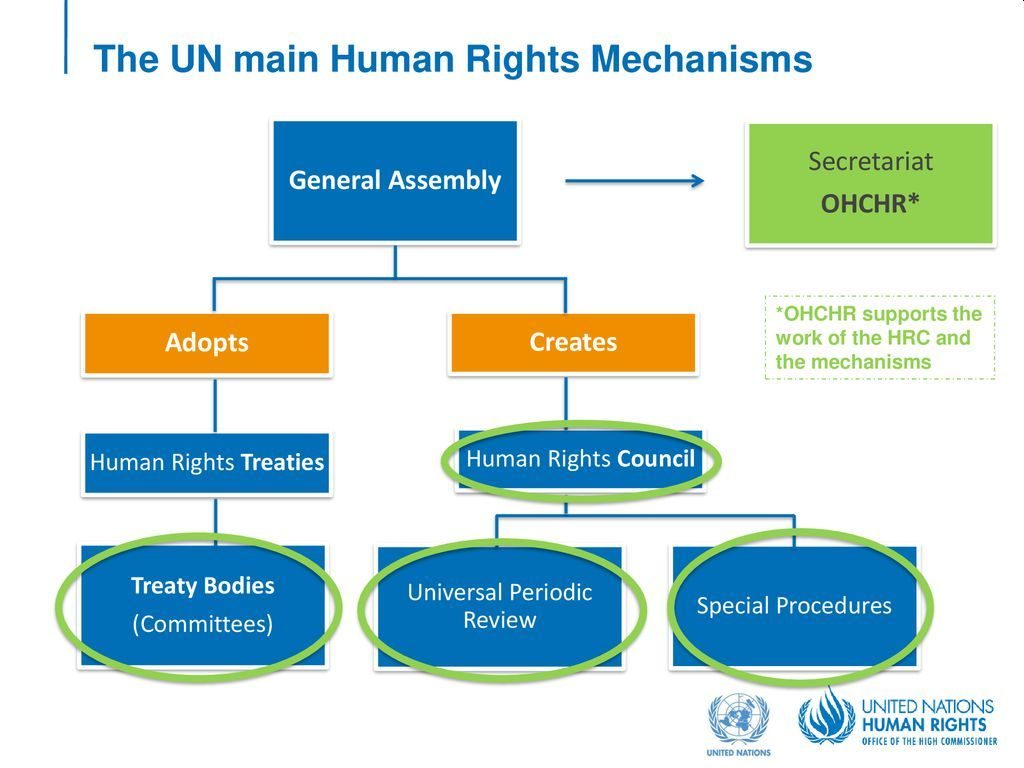

The brainstorming process concerns the procedures and mechanisms:

- the Special procedures (cf. the draft resolution on the special procedures circulating for a possible adoption during the September 2019 session of the HR-Council;

- the treaty bodies (in particular the way to the 2020 review);

- the Universal Periodic Review (this mechanism became a top priority for almost all stakeholders, and is not affected by the current financial constraints);

- the High Commissioner and her Office (OHCHR) (increasingly used by NGOs and defenders from the regions as a mechanism for progress at domestic levels);

- and the HR-Council (and its ongoing review).

Thesis to start the brainstorming

We propose to consider that there are seven simultaneous crises:

- First, a normative crisis: powerful Governments openly contest the validity of UN human rights norms;

- Second, a protection crisis: human rights are being grossly violated in many parts of the world while powerful governments argue for dialogue and cooperation with the perpetrating governments;

- Third, a leadership crisis: who now provides leadership in defence of universality and of the norms and institutions patiently built up over the past seven decades;

- Fourth, a political crisis: aided by some officials, powerful Governments are actively seeking to dismantle the policies and institutions established over the past 70 years. This includes control of the human rights treaty bodies, control of the human rights special procedures, control of the HR-Council and the UPR process;

- Fifth, a financial crisis: powerful Governments are deliberately squeezing human rights organs through financial cuts and other pressures;

- Sixth, a crisis involving continued pressures on NGOs: NGO space for operating at the UN is being constantly curtailed, while NGOs seeking to defend human rights are openly attacked;

- Seventh, a crisis stemming from the non-engagement of the UN Secretary-General in defending the third UN pillar, human rights, alongside the pillars of peace and development.

How is the human rights movement to overcome these seven crises ? This calls for deep reflection within the human rights movement.

acz-gdh-ghr-14.08.2019