Password : GHR-GSS-37 – Contact: info@gdh-ghr.org – +41 79 315 82 83

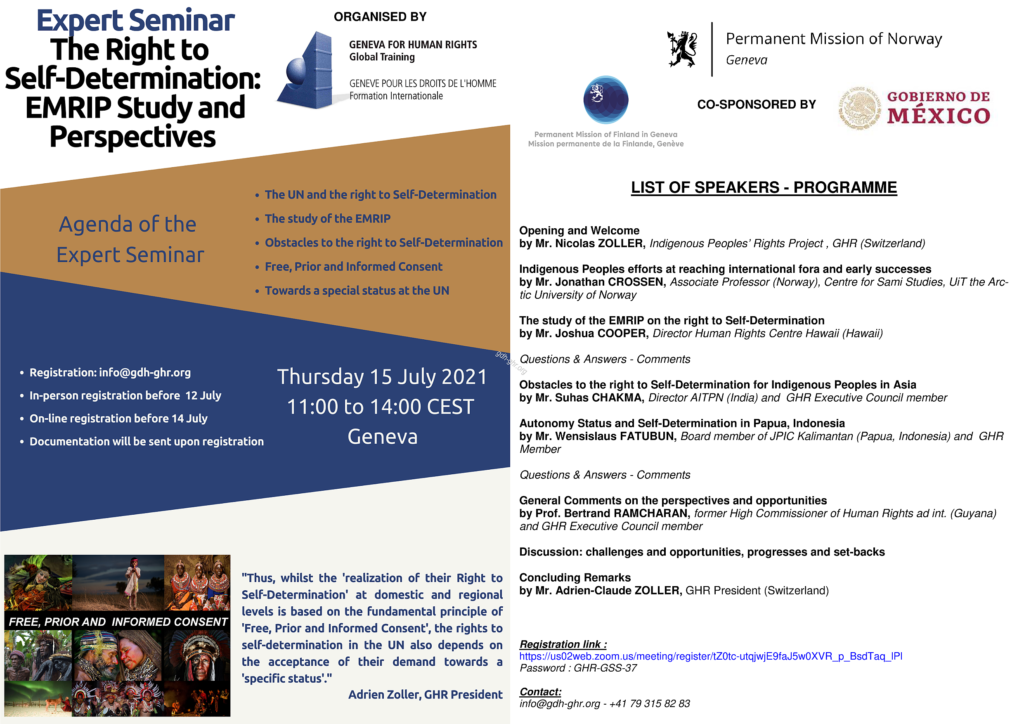

GHR convenes its 6th Expert Seminar on Indigenous Peoples’ Rights.

Thursday 15 July 2021 – from 11:00 to 14:00 CEST

Registration : https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZ0tc-utqjwjE9faJ5w0XVR_p_BsdTaq_lPl

Password: GHR-GSS-37

Please find hereunder the list of invited speakers and panellists:

Prof. B. RAMCHARAN,GUY, Former High Commissioner for HR

Mr. Joshua COOPPER, USA, Hawaï Institute for HR

Mr. Adrien-Claude ZOLLER, CHE, GHR President

Ms. Karla E. Kawenniiostha, USA, Indian Law Resource Center

Mr. Binota DHAMAI, BGD, EMRIP Member,

Mr. Suhas Chakma, IND, Director at Rights & Risks Analysis Group

Mr. Wenseslaus FATUBUN,IDN, Board member of the JPIC Kalimantan

Mr. Kenneth DEER, Canada, Secretary at Mohawk Naton

Prof. Jonathan CROSSEN, NOR, Centre for Sami Studies

Indigenous representatives are invited to speak and share about their experiences. We have also invited academics and practitioners to share their strategic foresight on the space for Indigenous Peoples within the UN and to assess the set-backs and progresses made in achieving the ends of the UNDRIP.

The event takes place during the 14th session of the EMRIP, the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (12 to 16 July 2021).

The programme of the Seminar has been tailor-made for on-line participants. It is also opened to in-person participation for those who are in Geneva.

The right to self-determination: the study of EMRIP and perspectives

The two International Covenants adopted by the General Assembly on 16 December 1966, on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (entered into on 3 January 1976), and on Civil and Political Rights (entered into force on 23 March 1976), have one Common Article 1 providing that:

| ‘1. All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development. 2. All peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources without prejudice to any obligations arising out of international economic co-operation, based upon the principle of mutual benefit, and international law. In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence’. |

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (General Assembly Resolution 61/295 of 13 September 2007) is the most comprehensive legal instrument detailing the rights of indigenous peoples in international law and policy. It contains minimum standards for the recognition, protection and promotion of these rights. It affirms the principle of non-discrimination and the right to self-determination: indigenous peoples have the right to freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development, to participate in decision-making in matters affecting them. States have the obligation to consult and cooperate with them to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them. The Declaration also recognizes indigenous peoples’ rights to their lands, territories and resources, including to those traditionally held by them but now controlled by others. By definition, indigenous peoples’ rights are collective rights.

In the Outcome Document of the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples (September 2014), the UN member States reaffirm their ‘solemn commitment to respect, promote and advance and in no way diminish the rights of indigenous peoples and to uphold the principles of the Declaration’ and commit themselves to a series of domestic public policies and steps in the UN.

The Outcome Document further recognizes the specificity of indigenous peoples and the need ‘to consult and cooperate in good faith’ with them ‘through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources’ (para 20). The Document also highlights ‘the importance of indigenous peoples’ health practices and their traditional medicine and knowledge’ (para 12); and that ‘the traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous peoples and local communities make an important contribution to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity’. It affirms and recognizes ‘the importance of indigenous peoples’ religious and cultural sites and of providing access to and repatriation of their ceremonial objects and human remains in accordance with the ends of the Declaration’ (para 27). It stresses ‘the importance of the participation of indigenous peoples, wherever possible, in the benefits of their knowledge, innovations and practices’ (para 22). It recalls ‘the responsibility of transnational corporations and other business enterprises to respect all applicable laws and international principles, including the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights’ (para 24).

Since they obtained the right to participate in UN meetings concerning them, firstly in the WGIP (1982), Indigenous Peoples’ Representatives insisted not only to be heard, but also to become full partners in the negotiations with the independent experts and diplomats. The draft Declaration adopted by the WGIP and by the Sub-Commission was also their draft. And when the Commission on Human Rights created a Working Group to re-negotiate the draft, they did their utmost to keep the text unchanged. Similarly, when the General Assembly prepared the 2014 World Conference, they insisted that one of the two Co-Facilitators of the Conference by an Indigenous Representative, They established an Indigenous Global Coordinating Group composed by the seven indigenous-identified social and cultural regions of the world, and held their Global Indigenous Preparatory Conference, which took place from 10 to 12 June 2013 in Alta, Norway.

Thus, whilst the realization of their right to self-determination at domestic and regional levels is based on the fundamental the principle of free, prior and informed consent, the rights to self-determination in the UN also depends on the acceptance of their demand for to have a specific status. Definitively, indigenous peoples are not NGOs, as they have their own territory, government and institutions. They currently have to use the Consultative Status with ECOSOC, which does not allow them to be recognised as self-governing institutions. This challenge is currently under discussion both at the HR-Council and at the UN General Assembly.